Working capital is one of the most powerful levers for performance – yet many improvement-efforts stall or fail to stick. The reason is rarely bad intent or lack of data. More often, it’s something harder to see: supply chain bias.

Supply chain bias arises when functions optimize for their own goals – sales padding forecasts, procurement chasing unit cost savings, operations hoarding stock – without considering the wider system. Each choice may feel rational, but together they create excess buffers, distort signals, and lock in more operating working capital than the business truly needs.

This article explores how supply chain bias creeps into day-to-day decisions, how to distinguish bias from genuine supply chain constraints, and what companies can do to break free. By tackling bias head-on, organizations can release trapped cash, improve agility, and align finance, operations, and supply chain around one common Setpoint for success.

Want to download this article for free?

Create a free account on My Academy Hub to download the article The Hidden Enemy of Working Capital: How Supply Chain Bias Drains Cash and Agility today.

Operating working capital (OWC) is one of the most direct levers for financial performance:

In theory, improvement should be straightforward. In practice, however, many programs deliver short-term gains only to stall-or even reverse-over time.

The reason is not a lack of effort or bad intentions. It lies in the natural fault lines across the supply chain:

Each function is acting rationally, pursuing metrics that make sense within its own domain. But when those actions are taken in isolation, they don’t add up to system-wide improvement. Instead, they add up to:

This paradox – where every function appears to be “winning,” yet the business as a whole is losing – is the hallmark of Supply Chain Bias.

It’s the hidden force that locks in higher working capital than necessary, undermines improvement, and leaves companies wondering why progress never seems to stick.

Become a Certified Working Capital Expert with our accredited course Managing Working Capital

Supply chain bias is the tendency for functions to optimize their own goals – sales chasing revenue, procurement chasing unit cost savings, operations chasing stability – without considering the broader system impact.

These decisions often make perfect sense locally, but collectively they trap cash, slow down flows, and undermine profitability.

The antidote is alignment around a company’s true Operating Working Capital (OWC) Setpoint – the optimal balance of healthy inventory, receivables and payables needed to support operations and strategy. Without this reference point, teams fall back on informal “safety nets” that feel protective but ultimately hold the business back:

While these tactics may relieve immediate pain, they create longer-term harm:

Think of it like packing extra supplies into a hiking backpack “just in case.” Each item feels protective, but the load makes you slower, less flexible, and more exhausted. Supply chain bias works the same way: buffers feel safe, but they weigh the organization down.

In the language of the Theory of Constraints, supply chain bias is a classic case of local optimization: improving one node at the expense of the whole network. The outcome is predictable – apparent wins at the function level, but systemic underperformance for the business as a whole.

Not all working capital needs are the result of bias. Some are inherent conditions and constraints built into the supply chain-lead times, production cycles, or customer payment practices. These realities set the baseline OWC requirement that every business must carry to function.

Bias, by contrast, is optional. It reflects subjective perceptions, risk aversion, or localized fixes layered on top of real constraints. Left unchecked, bias solidifies into habit – “the way we do things here” – and obscures the company’s true Setpoint.

The danger is subtle but serious: when bias is mistaken for constraint, leaders accept inflated working capital levels as inevitable. Cash gets trapped, agility erodes, and opportunities for improvement are lost.

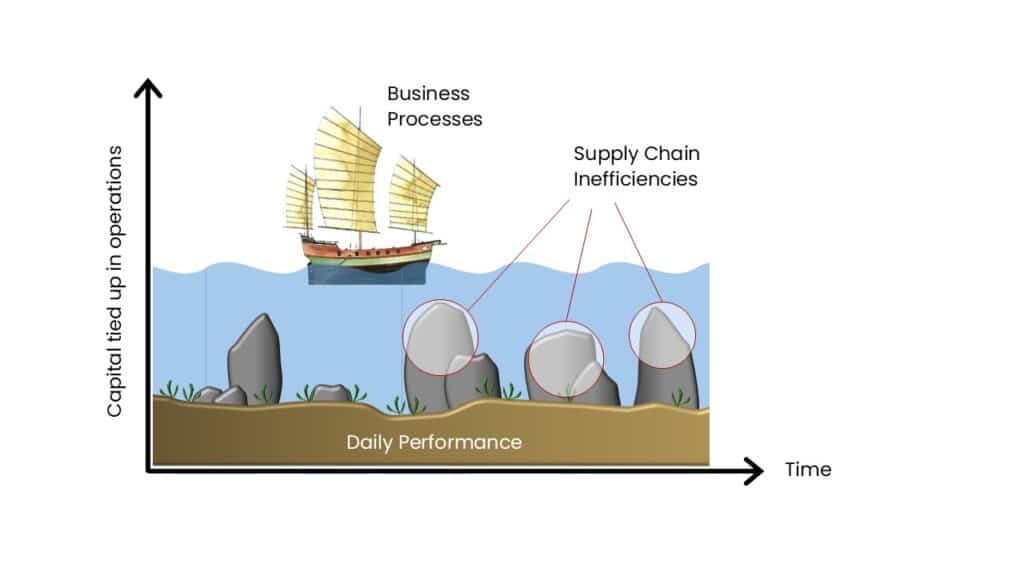

A useful way to picture this distinction comes from Lean philosophy – the classic “Japanese Sea” analogy:

When the water level is high enough, the rocks stay hidden – but they haven’t gone away. Many companies try to free up cash by draining the sea (reducing operating working capital) without first addressing the rocks (inefficiencies).

The result is predictable: the boat runs aground, service levels suffer, and the business quickly raises the water back up – often higher than before.

The real lesson? Constraints define the minimum; bias inflates the rest. True progress requires both identifying your Setpoint and methodically removing the rocks. Only then can the water be lowered safely, unlocking sustainable improvements in working capital, efficiency, and resilience.

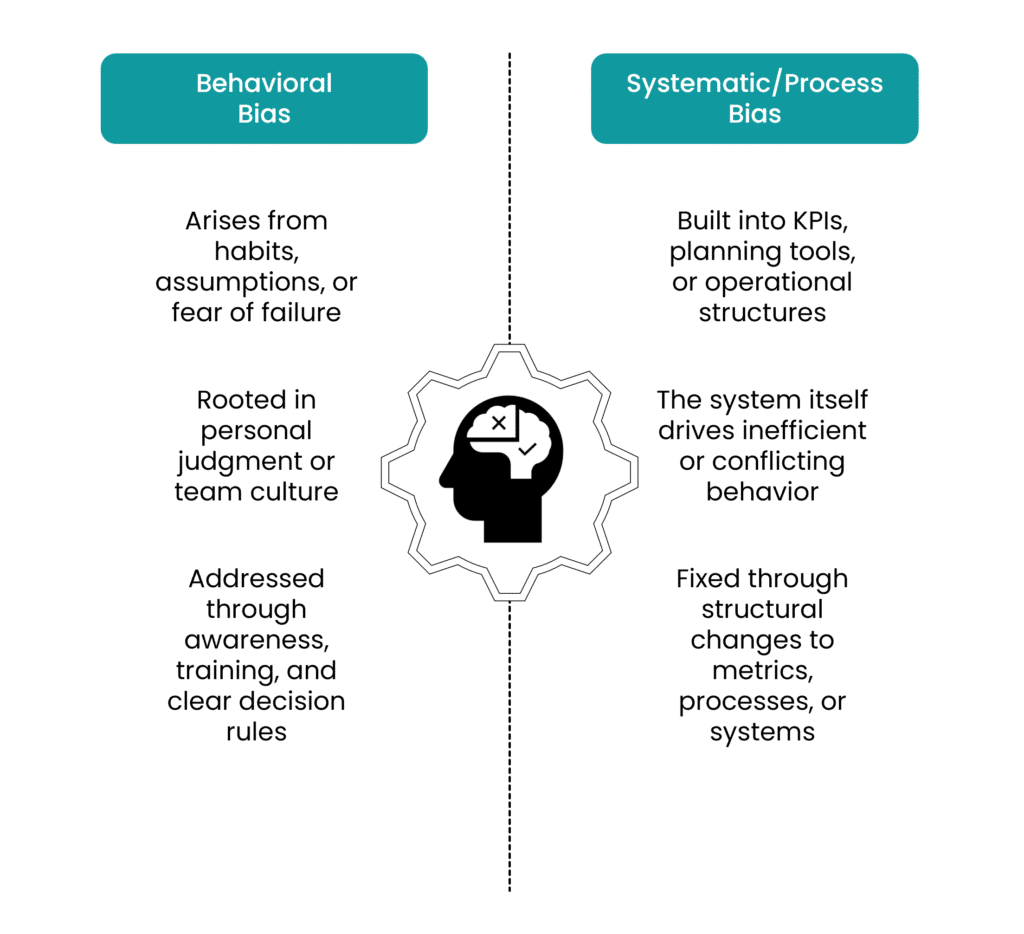

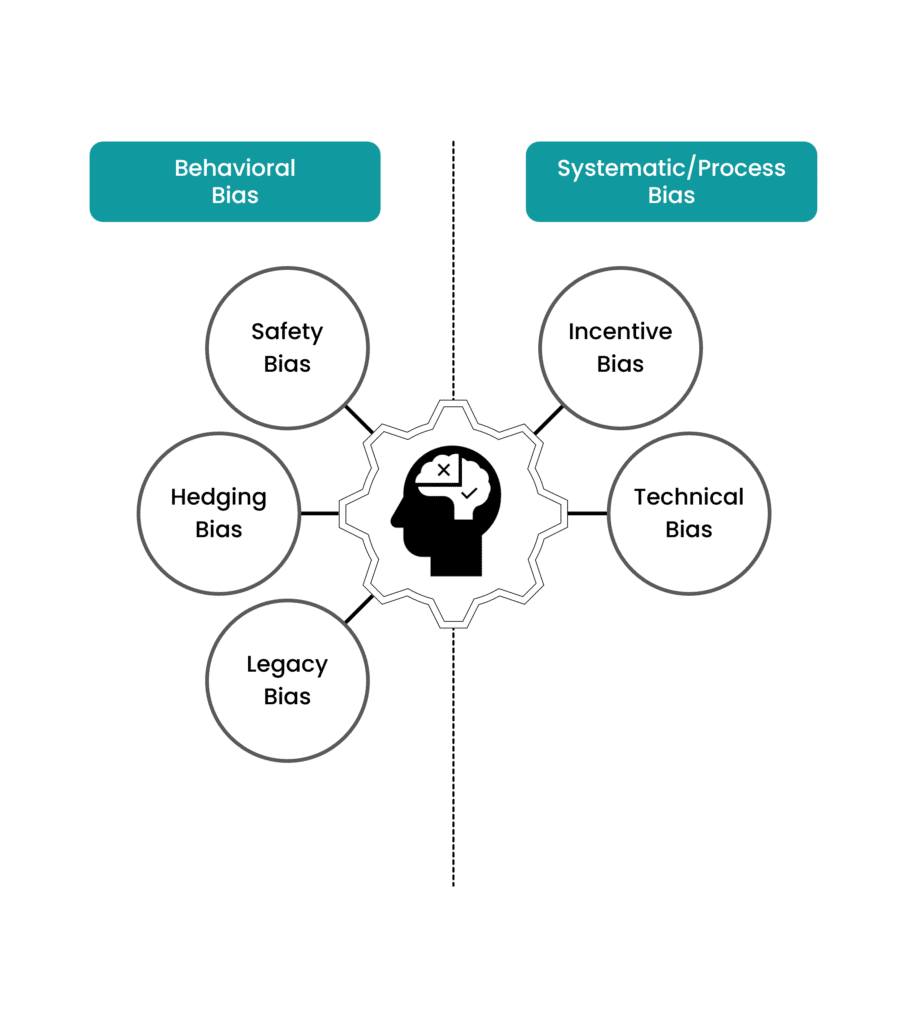

Not all biases are created equal. They tend to cluster in two categories – each requiring a different approach to fix.

These arise from human habits, assumptions, and cultural norms. They are often informal responses to risk or past experience:

Behavioural biases feel natural because they are rooted in judgment and memory. But they quietly accumulate, creating buffers that trap cash.

The remedy lies in awareness and discipline: training teams, challenging assumptions with data, and setting clear decision-making guidelines.

Systemic biases are different. They are hardwired into the way the business is run-baked into tools, KPIs, or planning structures:

Because these biases are structural, no amount of retraining will fix them.

The solution is redesign: aligning incentives across functions, updating planning logic, and ensuring data reflects reality.

Treating a systemic bias like a behavioural one – or vice versa – wastes effort and stalls progress. A planner trained to forecast more accurately will still distort demand if the KPI rewards over-forecasting.

Conversely, a new planning system won’t eliminate ingrained habits of over-ordering unless people are coached to trust it.

By recognizing whether a bias is behavioural or systemic, leaders can target the right corrective action-retraining individuals, redefining standards, or rethinking the very systems and incentives that shape decisions.

This is what transforms bias from an invisible drain on working capital into a visible opportunity for sustainable improvement.

Supply chain bias doesn’t live in theory – it shows up in everyday decisions.

Here are five recurring patterns that quietly inflate working capital and erode performance:

This occurs when teams add inventory buffers instead of addressing root causes.

This happens when teams exaggerate forecasts to safeguard resources or quotas.

Old experiences or unwritten rules become the default, even when circumstances have changed.

When KPIs reward local success at the expense of the whole system, bias takes root.

This arises when systems and parameters are not updated to reflect actual conditions.

These five biases are not the result of “bad actors.” They emerge from misaligned goals, incentives, and mental models that make local decisions seem rational. Left unchecked, they:

Recognizing these patterns is the first step. Challenging them – and redesigning the conditions that sustain them – is what turns operating working capital from a chronic drag into a strategic advantage.

While supply chain bias often shows up in day-to-day decisions – forecasting, inventory, purchasing – its roots frequently lie higher up in the organization: in the budgeting process.

We’ve seen this across industries: many companies struggle with operational inefficiencies and conflicting targets that originate indirectly, or even directly, from how budgets are set. The problem isn’t budgeting itself, but the way it is often performed.

When trust is missing, the process becomes a cycle of gaming and second-guessing:

This mistrust-driven budgeting dynamic often leads to:

In short, a dysfunctional budget process creates the very conditions – safety, hedging, and incentive biases – that inflate working capital and undermine agility.

An alternative is to design the budget as a trust-based, bottom-up process, where:

When budgeting is built on trust, alignment, and realism, it stops being a source of bias and becomes a catalyst for sustainable performance.

Eliminating supply chain bias is not about adding new rules or generating more reports. It’s about reshaping how the business thinks and acts – shifting from local optimization to system – wide alignment. That requires both a mindset shift and cross-functional collaboration.

Here’s how to start:

Establish the optimal levels of receivables, inventory, and payables for your business model, service goals, and risk tolerance.

Don’t just strip away buffers. First, understand why they were added – forecast errors, unreliable suppliers, poor visibility, or misaligned KPIs.

Move beyond siloed metrics. Procurement, sales, operations, and finance must share accountability for cash, cost, and service.

Why it matters: What gets measured gets done. Misaligned KPIs perpetuate bias; aligned KPIs dismantle it.

Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) should be more than a meeting – it should be the forum where trade-offs are surfaced, assumptions are tested, and biases are challenged.

Supply chain biases build up over years, often decades. Breaking them is not a one-off project but a continuous journey.

Supply chain bias cannot be eliminated by one function alone. It takes leadership commitment to set the reference point, align incentives, and foster collaboration.

The payoff is substantial: not only freed-up cash, but also improved agility, stronger trust, and a supply chain that performs as a system -not just a collection of parts.

Operating working capital is too important to be left to chance – or to the biases of individual functions. While finance may see it as a metric of liquidity, its roots lie deep in how the supply chain is planned, measured, and managed day to day.

The truth is simple but often overlooked: bias is optional, constraint is not. Every company will always carry some level of working capital because of its industry, operating model, and customer requirements. But much of what sits on balance sheets today is not necessity – its bias disguised as safety, efficiency, or best practice.

The companies that win are those that make bias visible, challenge it openly, and align the organization around its true Setpoint. That requires leadership courage, functional collaboration, and the discipline to fix causes instead of covering symptoms.

The payoff is not just freed-up cash. It is a supply chain that is leaner, more agile, more trusted, and ultimately more profitable. Breaking supply chain bias is not only a financial imperative – it is a strategic one.

Supply chain bias is the tendency for functions or individuals to optimize for their own goals - such as sales inflating forecasts, operations hoarding stock, or procurement chasing unit cost savings - without considering the wider system. These local decisions often feel rational but collectively inflate operating working capital (OWC), trap cash, and reduce agility.

Constraints are structural realities (e.g., lead times, production cycles, or customer payment practices) that set the baseline OWC a company must carry.

Bias is optional - subjective fixes, habits, or misaligned incentives layered on top of constraints. Bias creates unnecessary buffers and makes OWC higher than it needs to be.

Five patterns appear frequently across industries:

Because functions act rationally in silos - finance wants liquidity, operations want stability, sales want growth, procurement wants savings. Each goal makes sense in isolation, but together they create excess buffers, friction, and missed opportunities. This is the hallmark of supply chain bias.

Look for recurring patterns of excess buffers or persistent inefficiencies that aren’t explained by real constraints. Examples include:

Cross-functional reviews and benchmarking against a defined Setpoint can help expose where bias has crept in.

No single function can fix bias on its own. Success requires:

Ultimately, OWC should be treated as a shared operational responsibility, not just a finance metric.

Turn theory into practice and boost your career with accredited training. Become a Certified Working Capital Expert by enrolling in our flagship course: Managing Working Capital.

Categories