Want to download this article for free?

Create a free account on My Academy Hub to download the article Working Capital and the Cash Conversion Cycle today.

This article explains the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) – what it is, how it works, and why it is a critical measure of financial health.

The CCC shows how quickly a company can convert its investments in Operating Working Capital (OWC) – receivables, payables, and inventory – into actual cash.

Understanding this cycle is essential, because capital tied up in operations directly impacts the balance sheet and determines the amount of cash flow available to fund growth, pay debt, or build resilience.

Finally, the article explores why there is no universal definition of a “good” or “bad” cash conversion cycle. Instead, performance depends on the industry context and the company’s supply chain design, which shape what level of working capital is realistic and sustainable.

Strong profits don’t guarantee liquidity – the Cash Conversion Cycle reveals how effectively your business turns working capital into cash.

Become a Certified Operating Working Capital Expert with our accredited course Managing Working Capital

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) – also known as the Operating Working Capital Cycle or the Funding Gap – measures the number of days a company’s cash is tied up in Operating Working Capital (OWC) before it is converted back into cash.

In practice, it tracks three critical timeframes:

The CCC combines these components into a single metric that shows how efficiently a company manages its working capital cycle.

A shorter CCC means cash is released faster, improving liquidity; a longer CCC means more cash is locked in operations, reducing flexibility.

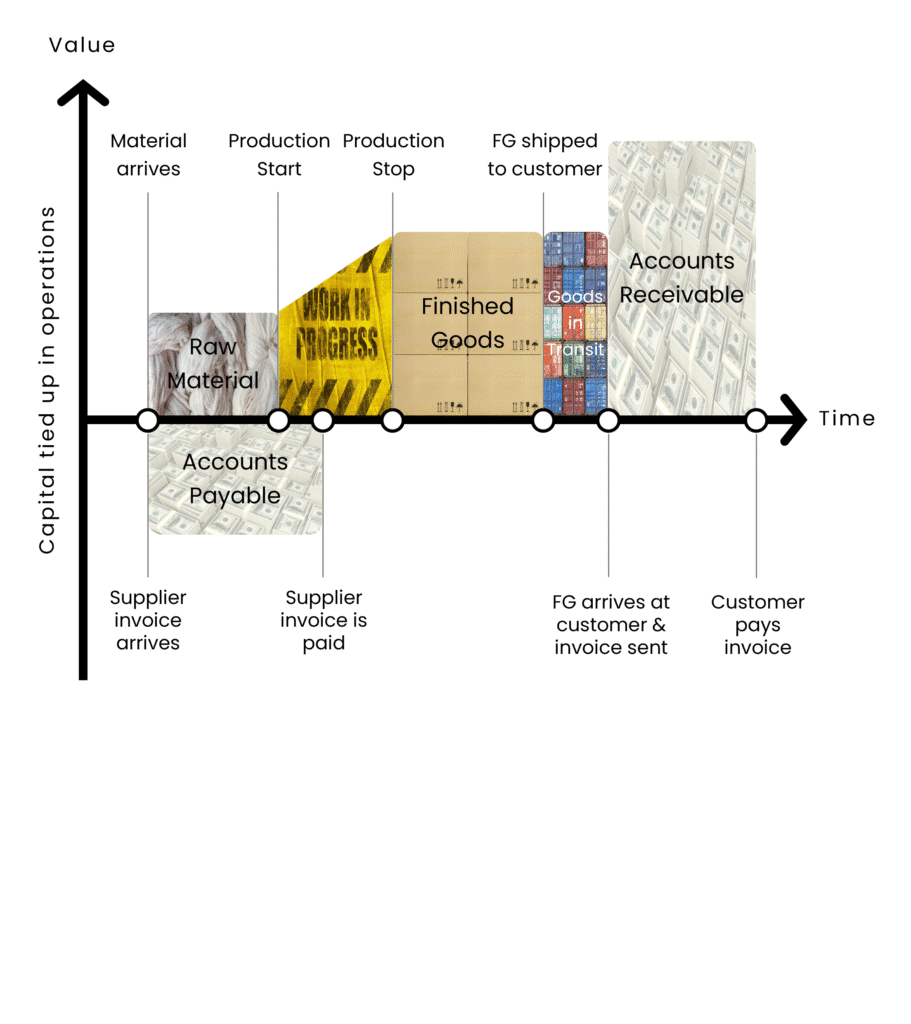

When discussing how cash can be tied up in operations, it’s important to understand the concept of operating working capital.

Operating working capital refers to the funds a company requires and must finance to support its day-to-day operations, including the procurement of raw materials, production processes, inventory management, and invoicing & collection.

Cash becomes tied up in operations primarily due to the time lag between various stages of the purchasing, production, and sales cycle. Let’s break down these core processes:

Overall, the entire cycle from procuring raw materials to receiving payment from customers represents a period during which cash is tied up in operations.

This working capital requirement is necessary to sustain the ongoing operations of the business but can also pose challenges, especially if the company faces cash flow constraints or operates with thin profit margins.

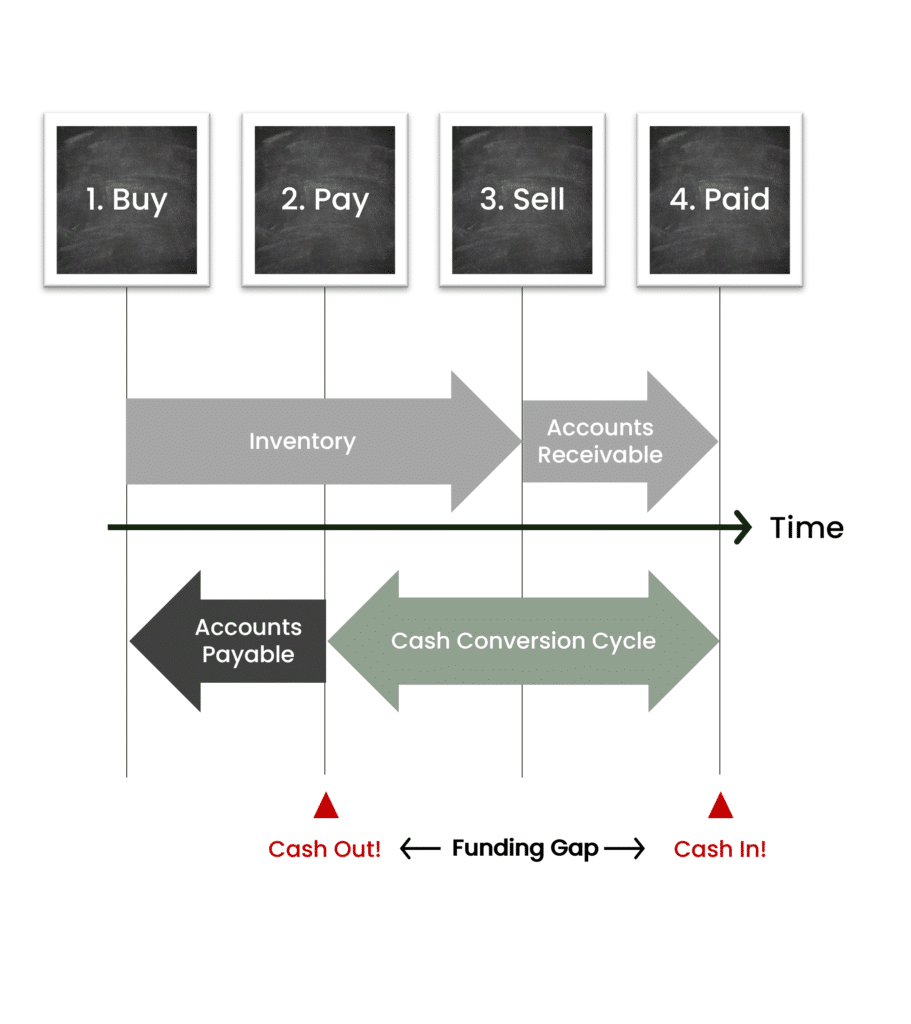

The Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) can be understood best as a timeline of cash movements through a company’s operations.

It starts when a business buys materials and ends when it finally collects cash from customers. In between, capital flows through different balance sheet accounts – inventory, payables, and receivables – each creating either a delay or a relief in the company’s liquidity.

Let us look at this as a timeline with four main events:

This sequence highlights how Operating Working Capital (OWC) moves through the business and why cash flow timing matters.

To understand these flows, let’s look at the key balance sheet accounts one by one and see how they affect cashflow in practice.

As soon as materials are purchased and processed, they sit on the inventory account until sold. During this time, cash is essentially frozen in inventory and cannot be used for other purposes.

The length of the arrow, or the time the material is held on the inventory account, depends on how long the material is kept on the shelves before being sold to a customer.

When material is bought on credit, the company won’t pay until after the agreed supplier credit period reaches its end.

The length of the arrow will reflect the credit time given. Say 30 days as an example.

Until the end of the credit period and payment is made, the value of the material is held on the accounts payable account. It is not until the credit period is over and actual supplier payments are made that cash outflow occurs.

When the customer buys on credit, payment is not made until after the credit period has ended. As with account payables, the length of the arrow reflects the credit time given.

When sold and invoiced, a product will leave the inventory account and the corresponding value will move to the accounts receivable, until the credit ends, and payment is made.

It is not until the credit period is over and customer payments are made that cash inflow occurs.

The total time between paying suppliers and receiving customer payments is the Cash Conversion Cycle. It represents the period during which the company must finance its own operations with internal cash or external funding.

This is why the CCC is sometimes also called the Funding Gap: it shows how long the business must bridge the gap between cash outflows to suppliers and cash inflows from customers.

The CCC encapsulates three key stages of a company’s operating cycle:

The CCC is therefore calculated using three other operating working capital metrics:

DIO and DSO are short-term assets, while DPO is classed as a liability.

CCC = Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO) + Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) – Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)

Where:

DIO = Inventory / Annual cost of goods sold (COGS) x 365

The Days Inventory Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company holds inventory before sold.

DSO = Accounts Receivable / Annual Sales x 365

The Days Sale Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average a company takes to receive payments for its sales.

DPO = Accounts Payable / Annual COGS x 365

The Days Payable Outstanding metric is a measure of how many days on average it takes a company to pay its suppliers.

CCC = DIO + DSO – DPO

DIO = Inventory / Annual cost of goods sold (COGS) x 365

DSO = Accounts Receivable / Annual Sales

x 365

DPO = Accounts Payable / Annual cost of goods sold (COGS) x 365

The Cash Conversion Cycle is a lens into how efficiently a company manages its operating working capital (OWC). It tells you how many days cash is tied up in receivables and inventory, offset by the credit received from suppliers.

The rule of thumb:

There is no universal definition of a “good” or “bad” CCC.

The Cash Conversion Cycle must always be interpreted in context. A short CCC might indicate efficiency in one sector or company but could be impossible – or even harmful – in another.

Here’s why:

1. Different Industry Dynamics – External Realities

2. Different Business Model – Strategic Choices

3. Different Supply Chain Setup – Design and Trade-Offs

These choices sit between external constraints and internal strategy, reflecting trade-offs between liquidity, service, and efficiency.

A company’s CCC only makes sense when viewed through its industry, business model, and supply chain context. What is efficient for one may be unsustainable for another.

The CCC is not just a financial ratio – it’s a practical management tool that can highlight risks, reveal hidden inefficiencies, and guide decision-making.

To make it actionable, companies should focus on following areas:

The CCC is not just a number – it’s a strategic indicator of how well profits are being converted into usable cash. By understanding what drives CCC, companies can identify whether liquidity challenges stem from receivables, payables, or inventory management – and act where it matters most.

Effective management of working capital is crucial for ensuring the smooth functioning of operations and maintaining financial stability.

Strategies such as optimizing inventory levels, negotiating favorable payment terms with suppliers, improving accounts receivable collection processes, and efficient production scheduling can all help minimize the amount of cash tied up in operations and improve overall liquidity.

Strategies to reduce a company’s cash conversion cycle could include:

By implementing the above strategies, a company will improve its working capital and strengthen its financial position, ultimately enhancing its ability to meet short-term obligations and support long-term growth.

However, it is important to recognize that a company’s cash conversion cycle cannot be viewed in isolation; it also reflects the interactions with suppliers and customers.

For example, when a company extends or delays payments to its suppliers, this will negatively affect the supplier’s cash conversion cycle by increasing their DSO.

This could, in turn, create cash flow challenges for the supplier, potentially leading to future price increases or impacting on their ability to meet orders on time and in full.

The Cash Conversion Cycle is more than an accounting metric – it is a window into how effectively a company turns operating working capital into cash.

Success lies in managing CCC holistically: aligning functions, tracking trends, and connecting high-level ratios to operational realities. Companies that actively measure, understand, and improve their CCC gain not only stronger cash flow but also a lasting competitive edge.

Turn theory into practice and boost your career with accredited training. Become a Certified Operating Working Capital Expert by enrolling in our flagship course: Managing Working Capital.

Categories