Most companies don’t lack data, tools, or commitment when it comes to operating working capital improvement. They run inventory projects, tighten payment terms, upgrade planning systems – yet results rarely last. Gains fade. Buffers return. Finance pushes harder, operations resist stronger, and leadership wonders why progress never sticks.

We believe the real barrier isn’t operational complexity. It’s cognitive. It’s cultural.

It’s Supply Chain Bias – the silent force inside every organization that turns rational decisions into systemic inefficiency.

Most companies don’t have a working capital problem. They have a bias problem.

And once you see it – you can change it.

Breaking through Supply Chain Bias is hard!

Find out how in the full article: The Hidden Enemy of Working Capital: How Supply Chain Bias Drains Cash and Agility

Across industries, every function acts with good intent:

Each team is “winning” on its own metrics. Yet the business as a whole is losing – carrying more inventory, cash, and friction than it needs. This is the hallmark of Supply Chain Bias: when local optimisation overwhelms system performance.

Operating working capital doesn’t stall because people are careless. It stalls because the system quietly encourages bias over alignment.

Supply Chain Bias is not a mistake or a failure of expertise. It’s the accumulation of assumptions, habits, and incentives that inflate operating working capital beyond what the operation truly requires.

Individually, these actions feel prudent. Collectively, they trap cash.

To improve operating working capital sustainably, leaders must separate constraints (the structural limits of the supply chain defining a company’s operating working capital requirements) from bias (the self-imposed behavior sitting on top of them).

At Working Capital Hub, we define four legitimate constraints that every supply chain must respect.

The Four True Constraints (Non-Negotiable):

| Constraint | What it Represents | Bias (Self-Imposed, Optional) |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Time | The time it genuinely takes to source, produce, or deliver | Extra “just in case” inventory to cover perceived delays |

| Capacity | The genuine throughput limit of resources or equipment | Running at full capacity or overproducing to “stay efficient” even without demand |

| Complexity | The variety and variability inherent in the portfolio or process | Optimizing individual sites/product lines instead of total flow (fragmented safety stock everywhere) |

| Predictability | The volatility of demand and supply you cannot eliminate | Forecast padding and manual overrides to protect against uncertainty rather than improving the signal |

While the examples below focus on inventory, the same logic applies to receivables and payables – where perceived “constraints” often mask bias in credit terms, payment practices, and customer negotiations.

In Accounts Receivable, bias may show up as extended credit beyond policy “to protect relationships.” In Payables, it may appear as blanket term extensions that damage trust rather than address underlying cost or process inefficiencies. The principle remains the same: constraints are real, bias is optional.

If a buffer cannot be justified by one of these structural realities, it is excess. It is optional. And it can be unwound.

Most companies believe their working capital challenges are driven by structural issues – long lead times, unpredictable demand, complex supply chains. In reality, what holds them back is not constraint, but bias.

Bias is dangerous precisely because it hides behind responsibility. It doesn’t announce itself as inefficiency. It presents as caution, best practice, or professional judgement. It lives in planning files, budget cycles, supplier contracts, and unwritten rules no one remembers creating.

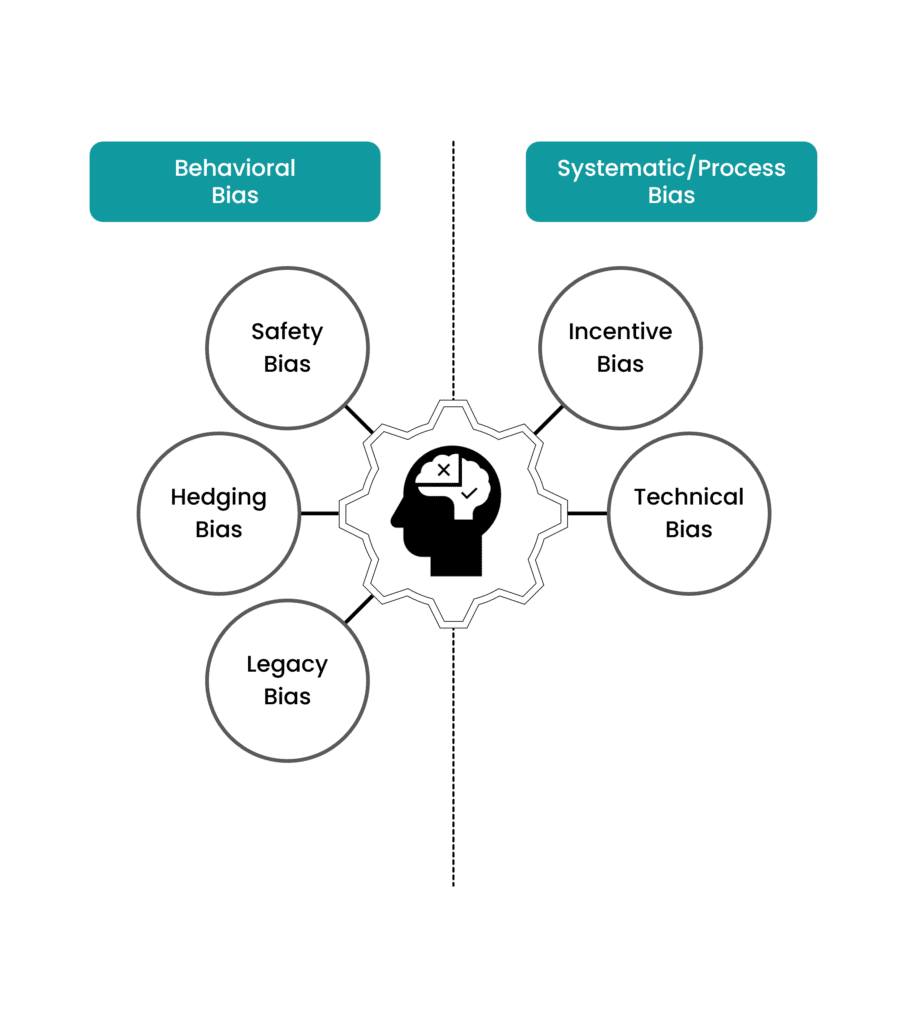

At Working Capital Hub, we classify Supply Chain Bias into five recurring patterns:

Each one feels rational in isolation. That’s how bias survives – under the banner of “responsibility.”

And this is also where most operating working capital programs go wrong. Under pressure to deliver quick results, they default to “cheese cutter” tactics – top-down targets like “reduce inventory by 10%” – applied uniformly across the business. These programs focus on removing buffers, not removing the reasons buffers were created.

The consequences are predictable:

The critical question is not “How much can we cut?” – it is “Why was it added in the first place?”

Until leaders confront that question, working capital will always grow back.

The Operating Working Capital Setpoint establishes a shared definition of “enough,” based on real constraints, not inherited fear. Without it:

Finance pushes for less

Operations pushes for more

Sales pushes for protection

The Setpoint replaces defensive buffers with deliberate choices. It shifts the conversation from pressure to precision – from cutting to calibrating.

Supply Chain Bias cannot be fixed by a single function. It requires executive sponsorship – leaders willing to:

When bias is exposed and aligned decisions are made, operating working capital improves naturally. Not through force, but through precision.

However, until leaders define ‘enough,’ teams will keep defending ‘more.’ Bias fills every gap that leadership leaves empty. Real leadership isn’t about demanding less operating working capital — it’s about knowing how much you truly need.

Where to Go Next

This article introduces the concept of Supply Chain Bias. To go deeper:

Take the course Masterclass – Managing Working Capital at the Hub’s learning center My Academy Hub and gain the skills to turn liquidity into growth and resilience.