Want to download this article for free?

Create a free account on My Academy Hub to download the article Accounts Payable: Complete Guide, Metrics & Best Practices today.

Accounts Payable (AP) is far more than a line item on the balance sheet. It represents supplier credit – a form of short-term financing that allows businesses to defer cash outflows, optimize liquidity, and strengthen working capital.

Managed well, AP frees up cash to fund growth and investments while maintaining strong supplier relationships. Managed poorly, it creates hidden risks, missed opportunities, and distorted financial insights.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of Accounts Payable: from the basics of what AP is, to process design, key metrics, strategic management practices, and advanced insights from transactional data analysis.

Become a Certified Working Capital Expert with our accredited course Managing Working Capital

Accounts Payable (AP) refers to the outstanding bills and obligations a company owes to its suppliers and service providers. It is recorded as a current liability on the balance sheet, typically due within 30–90 days.

At its core, AP functions as a form of interest-free short-term credit extended by suppliers. By delaying outflows, businesses conserve cash that can be deployed elsewhere in operations.

A company’s AP profile is directly linked to the commercial terms it negotiates and enforces with suppliers.

Longer terms = more time to hold cash before payment is due.

Common AP obligations include:

The common AP obligations can be grouped into:

Why the distinction matters:

Supplier payment terms define the agreed timing of when a buyer must settle an invoice relative to the invoice date or delivery. They specify how long a company can hold onto cash before payment is due. Terms can range from advance payment or cash on delivery, to Net 30, Net 60, or longer credit periods. In practice, payment terms shape both the supplier’s liquidity and the buyer’s working capital position.

Businesses use a variety of structures to govern how and when payables are settled. Examples of such payment terms include:

| Term Type | Trigger Date | Typical Use Case | Impact on Cash Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advance Payment | Before delivery | Made-to-order goods, custom manufacturing, upfront services | Protects supplier; increases buyer’s upfront cash need |

| Cash on Delivery (COD) | At delivery / receipt of goods | New customers, high-risk buyers | Supplier gets cash immediately; no credit period for buyer |

| Net Days (e.g., Net 30/60/90) | Fixed days after invoice date | Standard across industries; larger buyers push for longer terms | Extends buyer liquidity; delays supplier inflows |

| End of Month (EOM) | End of the invoice month | Synchronizes with monthly closing cycles | Predictable for both parties; may shorten/lengthen cash cycle depending on issue date |

| Early Cash Discounts (e.g., 2/10 Net 30) | Within discount window (e.g., 10 days) | Suppliers use to speed up cash collection; buyers weigh benefit if discount % exceeds their cost of capital | Buyer reduces cost if discount > cost of capital; reduces liquidity sooner |

The original purpose of payment terms is to balance cash flows between buyers and suppliers:

While AP tracks what a business owes suppliers, Accounts Receivable (AR) tracks what customers owe the business:

| Accounts Payable (AP) | Accounts Receivable (AR) |

|---|---|

| Money owed to suppliers | Money owed by customers |

| Classified as a current liability on the balance sheet | Classified as a current asset on the balance sheet |

| Represents a supplier credit obligation | Represents customer credit sales |

| Positive impact on working capital - delays cash outflows and conserves liquidity | Negative impact on working capital - ties up cash until customers pay |

Together with Inventory, AP and AR form the backbone of working capital dynamics.

In recent years, regulators have recognized the power imbalance between large buyers and smaller suppliers when it comes to payment terms. As a result, restrictions have been introduced in various jurisdictions:

While regions like the EU apply common directives, individual countries enforce more or less strict regimes:

The takeaway: while AP policies can be designed with a global lens, compliance and supplier relationships must be managed locally, with full awareness of the legal frameworks and business norms in each market.

For detailed legal and regulatory differences by country, see this country-by-country payment terms overview from Taulia.

Payment terms are not just an administrative detail on an invoice – they are a strategic lever that shapes cash flow, supplier stability, and business competitiveness. The way a company manages its terms reflects its financial discipline, operational efficiency, and its approach to building trust across the supply chain:

In other words, AP management sits at the crossroads of finance and supplier partnership.

Payment terms should protect the buyer’s liquidity without undermining supplier stability. Companies that thrive are those that use their leverage responsibly – not by stretching or over-extending terms, but by building balanced partnerships that strengthen the entire supply chain.

Accounts Payable is sometimes misunderstood. It is not an expense. Expenses appear on the income statement when resources are consumed in generating revenue. AP, on the other hand, represents the obligation to pay suppliers and is recorded as a current liability on the balance sheet until the invoice is settled.

Day 1: Purchase on Credit

Day 30: Materials Are Used in Production

Day 60: Invoice Payment

This flow shows why AP is not classified as an expense: it is the temporary liability that bridges the timing between purchase and payment.

AP plays a central role in working capital management because it:

But using supplier credit requires discipline:

Consistency in applying terms signals financial reliability and strengthens supplier partnerships.

In short: Accounts Payable is both a financing tool and a relationship lever – it protects liquidity while influencing supplier trust and resilience.

Try our free P2P Self-Assessment Tool and uncover strengths, gaps, and opportunities for improvement.

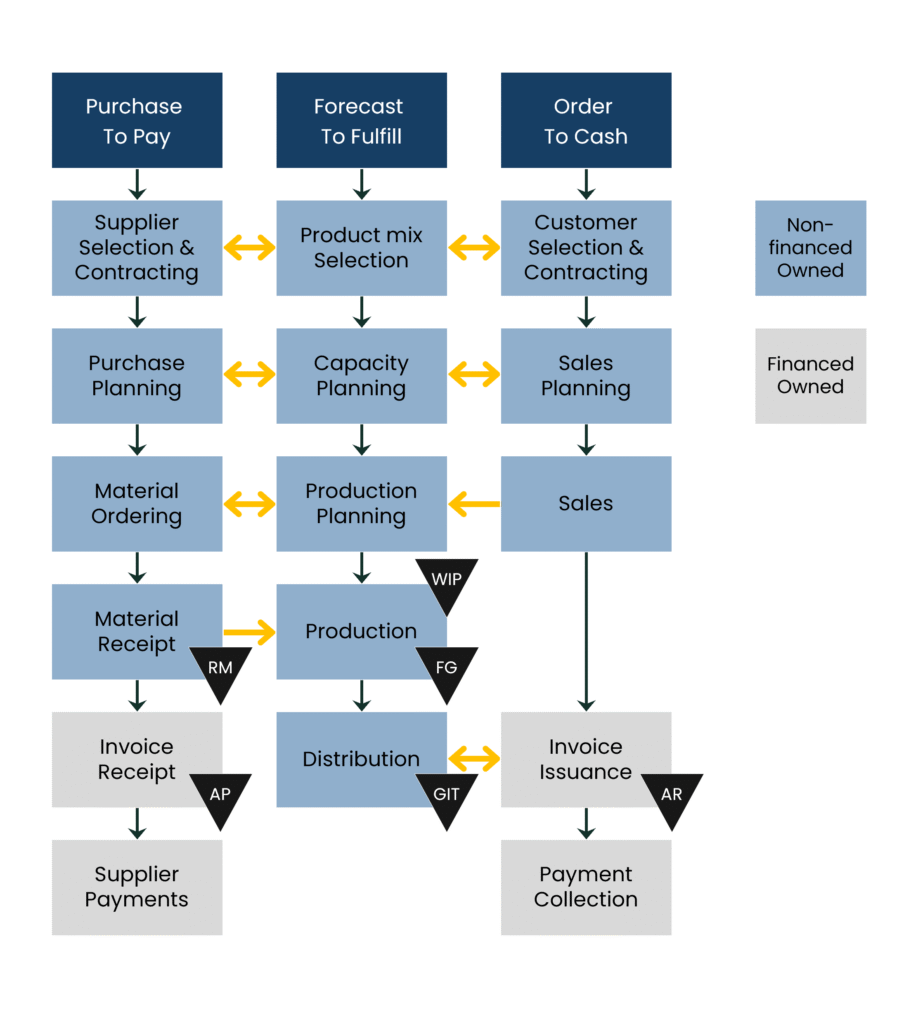

The Purchase-to-Pay (P2P) cycle covers the entire process of procuring goods or services and settling the resulting obligations. It is the operational backbone that generates Accounts Payable.

Key point: The level and quality of AP on the balance sheet is a direct consequence of how well the P2P cycle is managed. Each step – from negotiation to payment – influences cash flow, working capital, and supplier relationships.

Despite its importance, the P2P process often suffers from weak alignment and poor visibility. Typical challenges include:

Accounts Payable cannot be managed in isolation. The P2P cycle is tightly linked to other core processes:

Example: A company improves unit price and secures longer payment terms by committing to larger order batches. On paper, AP looks better. But if this decision is not aligned with sales forecasts, production cycles, or inventory targets, it creates excess stock, lengthens the cash conversion cycle, and increases financing needs.

A well-managed P2P process ensures invoices flow seamlessly, data is accurate, and payment practices align with company policy. But true effectiveness comes when P2P is managed holistically, in sync with F2F and O2C, so local purchasing decisions do not create hidden costs in working capital or liquidity.

Traditionally, two accounting metrics are used to assess how a company manages its payables: the Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio (APT) and Days Payable Outstanding (DPO).

The Accounts Payable Turnover ratio (APT) shows how many times per year a company settles its supplier obligations:

AP Turnover Ratio = Net Credit Purchases / (Average) AP

While useful in theory, the measure is abstract and provides little practical guidance for managers.

Days Payable Outstanding (DPO) expresses the same relationship in terms of days:

DPO = (Average) AP / COGS × 365

Example: A DPO of 55 means the company, on average, pays suppliers 55 days after purchase.

Unlike the turnover ratio, this measure is directly comparable to contractual payment terms, industry benchmarks, and regulatory limits. For this reason, most practitioners focus on DPO rather than APT.

DPO is also one of the three core levers of the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC), alongside Days Sales Outstanding (DSO) and Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO). Together, these metrics show how effectively a company converts its operating capital into cash.

For a full breakdown, see our separate guide to the cash conversion cycle here:

In practice: DPO is the more relevant headline measure, but organizations serious about working capital management increasingly rely on transaction-level data to uncover the reality behind the averages.

Traditional AP metrics like Days Payable Outstanding (DPO) and the AP Turnover Ratio are useful at a high level, but they often mislead.

Example: A company reports a rising DPO, which appears to signal stronger performance. Yet when transactions are analyzed, the truth emerges: applied payment terms are actually shorter, invoices are frequently paid late, and many “wild purchases” are made outside policy.

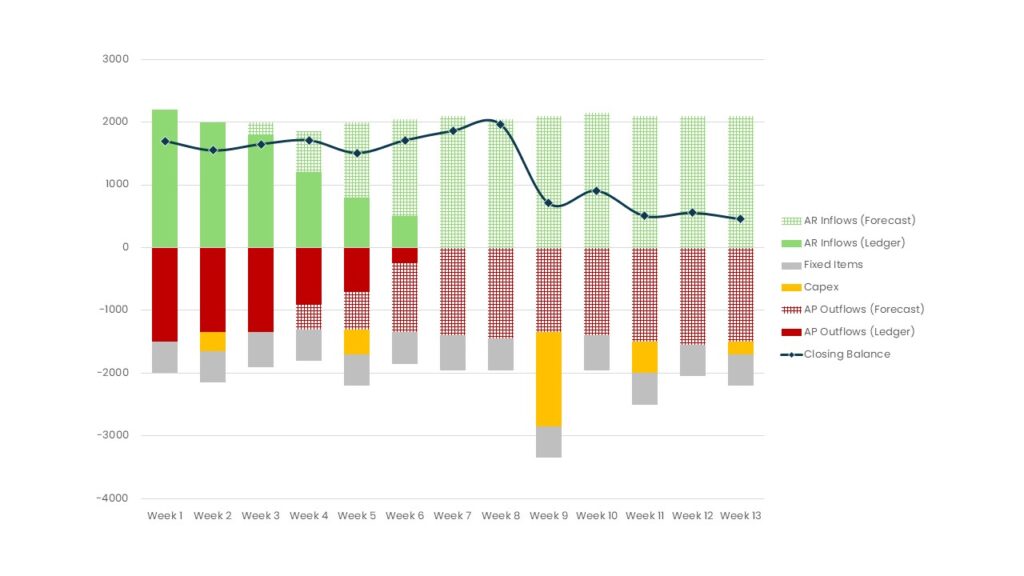

To move beyond averages, companies increasingly use transaction-level analysis of their payables. Instead of looking only at balance sheet metrics, this approach examines every supplier invoice to reveal actual performance against agreed terms.

Some of the most powerful insights come from metrics like:

This type of analysis helps companies detect early payment leakage, supplier non-compliance, off-policy purchases, and bottlenecks in invoice approvals.

For a step-by-step walkthrough of how to structure and run such an analysis – including the data needed and how to calculate these metrics – see our Masterclass: a step-by-step guide to AP Transaction Data Analysis.

A mid-sized manufacturer reported a steady increase in DPO, rising from 58 to 62 days. On paper, it looked like a success: more cash conserved, improved working capital.

But a transaction-level review told a very different story:

The true weighted average payment term was closer to 48 days – well below the policy standard of 60 days.

Suppliers had successfully pushed through shorter terms, often accepted by buyers without resistance.

Off-contract “wild purchases” further eroded liquidity discipline.

The apparent rise in DPO was driven by month-end effects, amplified by consistent late supplier payments – used to optimize reported metrics and liquidity, not actual performance.

Lesson: Balance sheet KPIs created a false sense of progress. Transactional analysis exposed weak policy enforcement, deteriorating supplier discipline, and a widening gap between strategy and practice.

Takeaway: Accounts Payable must be managed strategically, not mechanically. Metrics like DPO are useful signals, but only disciplined processes and transaction-level insight ensure AP fulfills its dual role: a source of interest-free financing and a foundation for healthy supplier partnerships.

Accounts Payable management is not just about processing invoices. It is about aligning payment behavior with financial strategy – optimizing cash flow while safeguarding supplier trust and operational resilience.

Accounts Payable is evolving rapidly – from a transactional back-office task into a strategic lever of finance, operations, and supply chain management. Several trends are shaping its future:

Accounts Payable is not simply about “paying the bills.” It is:

Companies that elevate AP management from routine bookkeeping to data-driven strategy unlock:

Short answer: It’s a liability, because it represents money owed to suppliers, not money owned by the company.

AP = invoiced obligations; accrued = obligations incurred but not yet invoiced. Both are liabilities, but recorded differently.

Trade = direct materials tied to production; non-trade = overheads/services. Trade payables impact COGS and CCC more directly.

A control step matching PO, goods receipt, and invoice to prevent errors or fraud. Core to AP discipline.

Payment terms are more than administrative details. They define expectations between buyer and supplier, reinforcing trust and goodwill. Reliable delivery must be matched by reliable payment. Well-structured terms protect cash flow for both parties and ensure that obligations are met without unnecessary strain.

Payment terms are negotiated between buyer and supplier. While the supplier usually proposes terms on the invoice, the final agreement depends on factors such as purchase volume, bargaining power, relationship history, industry norms, and regulatory requirements. Larger buyers often use their leverage to extend terms, while smaller suppliers may push for faster payment to safeguard liquidity.

Yes, payment terms are often abbreviated:

Failing to meet agreed terms can damage supplier relationships, trigger late payment penalties, and in some jurisdictions breach legal requirements. For buyers, consistently paying late may reduce negotiating power, harm reputation, or limit access to favorable terms in the future.

Payment terms directly influence liquidity. Longer supplier terms reduce the cash needed up front, freeing up working capital, while shorter terms or early payments increase cash requirements. Aligning Accounts Payable with Accounts Receivable and inventory cycles is essential to managing the cash conversion cycle effectively.

Turn theory into practice and boost your career with accredited training. Become a Certified Working Capital Expert by enrolling in our flagship course: Managing Working Capital.

Check out all Working Capital Hub Insights here