Want to download this article for free?

Create a free account on My Academy Hub to download the article Working Capital and Cashflow today.

Cash is the oxygen of business. A company can report strong profits but still face financial distress if it cannot generate enough cash to cover its day-to-day obligations. Salaries, supplier payments, loan repayments, and investments all require cash, not just accounting profit.

One of the most critical links between profit and cash is Working Capital. More precisely, Operating Working Capital (OWC) shows how much money a company has tied up in receivables, payables, and inventory.

The speed at which these items are turned into cash is measured by the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) – the time it takes to convert outflows for inventory and payables into inflows from customer payments.

A longer CCC means cash is tied up for extended periods, negatively impacting a company’s cashflow. A shorter CCC means a company can recycle its cash faster, providing more flexibility for reinvestment and resilience.

Managing both the level of OWC and the efficiency of the CCC can make the difference between a company that is constantly short of liquidity and one that enjoys the flexibility to invest, grow, and weather shocks.

This fact sheet explains the relationship between operating working capital and cashflow, outlines the drivers that affect both, and illustrates the impact through clear examples.

Become a Certified Operating Working Capital Expert with our accredited course Managing Working Capital

Without generating enough cashflow, a company will find it difficult to conduct routine activities such as buying goods and services, paying its employee salaries, making investments, financing growth, or paying off debt.

Cash is in turn directly affected by a company’s ability to convert its net operating working capital assets into sales and customer payments.

Cashflow problems are a leading cause of corporate distress. Multiple studies highlight that many bankruptcies occur not because companies are unprofitable, but because they run out of cash.

Consider two businesses:

The lesson: profitability does not guarantee liquidity. The bridge between profit and cash is operating working capital.

Working Capital measures short-term financial health by comparing assets that can be quickly converted into cash with liabilities that must be paid soon:

While this broad measure includes items like cash and debt, financial managers often focus on Operating Working Capital (OWC) to evaluate liquidity from operations:

This definition focuses on how a company finances its operations:

Together, these determine how much cash is tied up in running the business.

Cash flow represents the net movement of money into and out of a business over a given period. It is not the same as profit.

A company may show profits on its income statement while still running out of cash if payments from customers are delayed, if inventory levels are high, or if large investments have been made.

Cash flow is detailed in the Cashflow Statement, which is divided into three main sections:

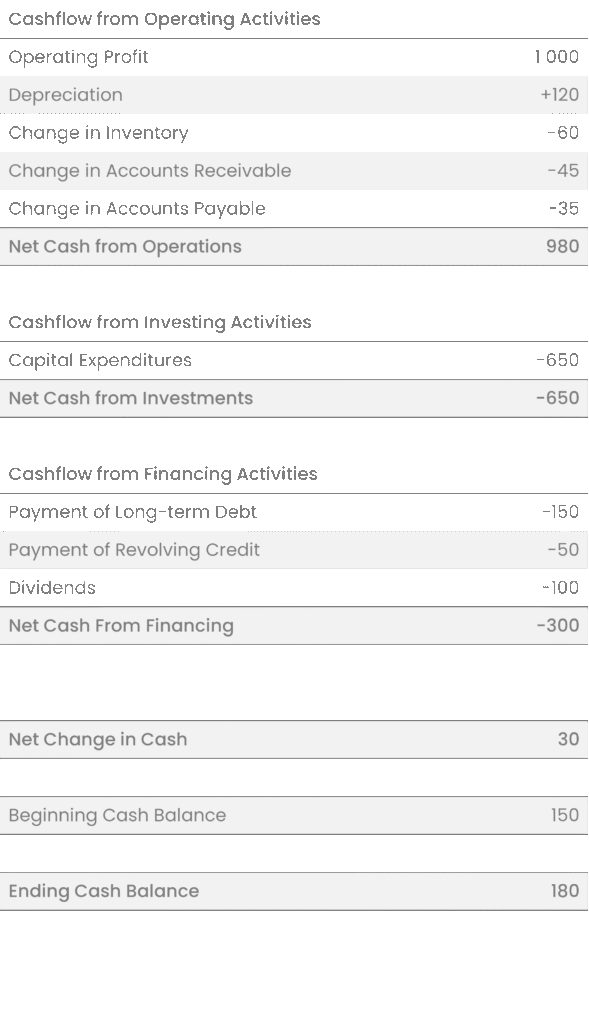

Example: Cashflow Statement

Of these, Operating Cash Flow is the most critical for day-to-day survival. It shows how much cash a company’s normal business activities generate after considering working capital needs.

Example: Profit vs Cashflow

A company sells $1 million worth of products in a quarter, but only half is paid in cash while the rest is on credit.

On the income statement, profit may look strong, but the cashflow statement shows only $500,000 in actual inflows.

If at the same time inventory increases and suppliers are paid early, the company may even report negative operating cash flow despite being profitable.

The link between Working Capital and Cashflow is straightforward but powerful: how a company manages receivables, payables, and inventory directly determines how much cash it has available

When Operating Working Capital (OWC) increases:

When OWC decreases:

Operating Cash Flow = Operating Profit + Depreciation & Amortization +/- Change in OWC

This formula highlights that profits alone do not equal cash. Depreciation and amortization are added back (they are non-cash expenses), while changes in OWC adjust for the timing of cash inflows and outflows from operations.

Why It Matters

Two companies with the same sales and profit can have dramatically different liquidity positions depending on how they manage OWC.

For example:

Key Insight

Operating Working Capital is the bridge between profit and cash flow. Efficient management of OWC ensures that accounting profits are actually converted into usable cash, which is critical for liquidity, resilience, and growth.

Movements in OWC are driven by three direct levers – Accounts Receivable, Inventory, and Accounts Payable – plus a set of structural and external drivers that influence those levers.

Inventory:

Accounts Receivable (AR):

Accounts Payable (AP):

While AR, Inventory, and AP are the immediate levers, several underlying forces determine how they behave:

Market and Customer Mix

Supplier and Operational Efficiency

Seasonality

Growth and Expansion

Structural and external drivers explain why working capital shifts over time. They highlight that managing OWC is not only about internal process control but also about adapting to market realities, operational efficiency, seasonality, and growth pressures.

Companies that anticipate these drivers can adjust early (e.g., negotiate better terms, align financing to seasonal cycles, or improve supply chain reliability) and avoid being surprised by sudden cash constraints.

Two manufacturing companies report identical sales and operating profit. At first glance, they look equally healthy.

However, differences in how they manage Operating Working Capital (OWC) dramatically change their cash position.

What Happened?

Why It Matters

Both firms show the same profit, but Company B has $10m more cash available at year-end. This difference is not just an accounting technicality – it can decide whether a company can:

Key Lesson

Profits do not equal cash.

How effectively a company manages receivables, payables, and inventory (it’s OWC) is often the difference between thriving and struggling.

Improving cash flow requires more than just focusing on receivables or delaying supplier payments.

It’s about holistic management of the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) – the time it takes to turn investments in inventory and receivables into cash, minus the time taken to pay suppliers.

By tackling each element of working capital in a structured way, companies can free up liquidity without harming operations.

Best Practice:

Regularly review these KPIs over time and benchmark them against peers and industry standards.

Early shifts in CCC or its components often signal liquidity risks or opportunities before they appear in the P&L.

Go beyond averages: analyze transaction-level data (e.g., invoice-level payment terms, customer payment behavior, supplier invoice patterns).

This provides a true performance view of OWC by uncovering hidden bottlenecks, systemic delays, or exceptions that aggregate KPIs can mask.

Key Lesson

Working capital management is not just a finance exercise – it requires cross-functional coordination.

By combining financial discipline with operational levers such as S&OP, forecasting, and supplier collaboration, companies can reduce the cash locked in operations and turn accounting profits into real, usable cash.

Operating Working Capital and Cashflow are tightly linked. Efficient working capital management frees up cash, reduces reliance on external financing, and supports long-term growth.

Companies that master this balance gain a significant competitive advantage: they are more resilient in downturns, better positioned to invest in opportunities, and less dependent on debt.

In short: profit is important, but cash is survival. Managing working capital effectively ensures both.

Turn theory into practice and boost your career with accredited training. Become a Certified Operating Working Capital Expert by enrolling in our flagship course: Managing Working Capital.

Categories